Monetize the Mountains

On that train, we learned that we could have been fined 100 francs each for “forgetting” our outbound train ticket, so we acquiesced and dropped some 40 francs together for one way’s 45 minute journey.

Hill people are, canonically, not impressive. In Lord of the Rings, they’re a bunch of ragtag “wild men” whom Saruman goads into attacking Rohan alongside the uruk-hai. In the U.S., the term “hillbilly” stands self-evidently apart from a Lowland William. In Switzerland, though, the hill people are very rich, and they brag about living in the mountains as opposed to the valleys.

I love the mountains. I love when land has texture, when one’s hands and feet can change their vantage point, when the tree species process with each step. I do not, nonetheless, get exactly how the Swiss pulled off this coup, reclaiming pride and largesse in hailing from the mountains the same way Mainers made lobster both expensive and coveted.

Alpinism, born in that mountain range home to some half dozen linguistic groups, is a natural venue for rivalry. In my pack alone, I tend to carry American, French, Italian, German, and Austrian gear. Reinhold Messner, one of the best ever, is Italian-born but speaks German. The first party up the Matterhorn was English. There's a top, and there's a clock, and it's easy to measure accomplishment.

Despite all this, I’ve only ever heard of the Swiss claiming to be the best. They say they're the best because they live in the mountains, whereas everybody else lives in the valleys. They are, therefore, the hilliest of hill people, yet they objectively hold the key to many expensive watches, no small number of vaults, and famously timely trains.

Headed into Switzerland with Emily, I hoped to interrogate this hypothesis. Suppose it was true, I wondered why these rich people with their banks and their chocolate would have run for the hills. Or if they had grown up in the mountains with their glaciers and rocky soil, I wondered how it was they became rich. Mountains and money did not, until the second half of the 20th century, go hand in hand.

The train journey from Paris to Interlaken required a change in Basel, and we figured that the place with the famous art stuff might be worth visiting. While backpacking, I’d often enjoyed open-handed hospitality from other thru hikers. This always reminded me of the emphasis that desert cultures traditionally place on hospitality, and I figured it was a symptom of extreme environments.

I had never heard the phrase “Swiss German Hospitality,” I’ll note. At 6:00 PM in Basel, every store was closed. We popped into three empty restaurants, each of which refused to sit us without a reservation. A fourth sat us way in the back, where potential mobsters listened to tinny music played from an iPhone 4’s built-in speakers. I had a terrific white asparagus risotto. Emily’s schnitzel was superb. We left promptly, talking in hushed tones.

Wandering through town, some of the Salzburgy colorful buildings had years on them, dating as far back as the 1300s and before. My first clue: the 14th century was the crescendo of the high middle ages, when the black death overtook Western Europe and the Monty Python-style feudalist incompetence appears to have crested, ahead of the Renaissance.

In England, say, if you didn’t have a castle or church, you probably had a thatched roof. Yet, these hill people were building quaint row homes that would fetch $4 million in Georgetown. Where did the money come from! The city was rather hilly, but could you say it was in the mountains?

Our train to Interlaken left on time, obviously. Along the way and at the station, we were bombarded by ads for “Jungfraujoch: Top of Europe.” This is evidently the railroad to the top of the Jungfrau, the tallest peak in the Bernese alps. In 1912, they installed a train that ran through the Eiger up to a saddle below Jungrau, the highest train station in Europe, at some 11,000 feet. In 1912! How! We filed it away in our back pocket and thought no more of it.

Our first day in Interlaken, we hiked around one of the lakes toward a waterfall, from where we hoped to grab a bus back to town. 100-odd years ago, they built a Shining-esque mega hotel so people could come and look at the waterfall for a month. By the time we got there, the bus had stopped running. A hotel employee sat in the parking lot behind the wheel of an empty van. He told us, without enough fake empathy, that he couldn’t call us a cab or give us a ride, and we’d have to walk another hour to Brienz, where a train would take us back to Interlaken.

This train from Brienz advertised the trip to Jungfraujoch: Top of Europe.

The next day, we hopped a train to Grindlewald, the mountain resort town at the base of Eiger, where there was supposed to be a glacial canyon to explore. The glacier, to our chagrin, had long since retreated. Yet, it once stuck out of the canyon far enough that they built another one of these hotels there.

Once we realized we would have to try a bit harder to find snow, we thought we’d investigate this Jungraujoch: Top of Europe racket.

It turns out they cost CHF 111 from Grindlewald without the Swiss Pass, which itself costs $267. They do not accept the Eurail pass. The guaranteed seat reservation costs extra.

We set off back to Interlaken without snow. On that train, we learned that we could have been fined 100 francs each for “forgetting” our outbound train ticket, so we acquiesced and dropped some 40 francs together for one way’s 45 minute journey.

Tired and ready to go home, the ads for Jungfraujoch: Top of Europe stung more and more.

Our third day, we took an extremely steep hike up the local hill in town, the Harder Kulm. It’s not a pun, but the hike is nontrivial. The funicular costs like 30 francs each way, so we and many others walked. The hike was fun, but we took the cable down so we could grab our stuff and jump on our train to Zermatt faster.

As we changed trains en route to Zermatt, the ads for Jungfraujoch: Top of Europe gave way to Zermatt Glacier Paradise.

Zermatt Glacier Paradise, reached only by cable car, is even higher than Jungfraujoch: Top of Europe.

In the U.S., Mount Washington has the Cog railroad. It and the other major East Coast peak, Klingman’s dome, have some roads to the top, but the majority fo the peaks on the West coast are not accessed by road, let alone rail.

These alternative, motorized routes make the mountains more accessible for a wider group of people. They also present a juicy opportunity to sell something nobody knew they needed. While we aren’t known for our habit of taking care of the disabled, one could be forgiven for expecting that Americans would monetize the mountains more.

Jackson, Tahoe, and other mountain resorts have their high season in the summers. People who don't ski or hike are content to roll up, get gouged on a hotel, sit on a bench, look at the mountains, and get gouged on dinner.

In Switzerland, they’re still keen to gouge you on the hotel and on dinner, and they have nicer benches. They’ve innovated this recliner that lets you stare up at the Matterhorn without craning your neck, and, my god.

But, they’ve also thrown in a remarkable network of gondolas, trams, cog railways, and lifts. All of these cost a king’s ransom, and they offer services that people in the American mountains weren’t exactly clambering for.

Some dolt of a reporter once incisively asked George Mallory, client of Tenzing Norgay, why he wanted to climb Everest, to which Mallory said “Because it’s there.”

This is an awfully 20th century English perspective. If you consider yourself to be the center of the universe, it’s easy to see why you might find a mountain’s existence to be a personal affront. The Swiss adaptation might be, “Why do you want to go to the top of Jungfrau?” and “because there’s a gondola.”

What we found in Switzerland were less the swashbuckling mountaineers of Chamonix or the dirtbag climbers of Yosemite but rather the most deft nature profiteers on the planet.

Our second day in Zermatt, before we had decided to try to get up to the Hornlihutte, the last stop before technical climbing on the Matterhorn, we found ourselves walking on a Ricola branded trail. The cough drops had been finished, but a set of metal advertisements still offered some light way finding, and some fun facts.

Walking up to the Matterhorn, we knew we were headed up a ski resort. Yet, at one point, we found a Gondola that stretched across a gorge to another massif below Dent Blanche, where it appeared to hit a dead end. No visible huts or other lifts, no way down the cliff, just a gondola for its own sake, with maybe a hiking trail behind it.

To the untrained eye, this is a tremendous waste of money.

Western tourism came of age in Central Europe, where the 19th century’s emerging leisure class went to the baths and the sanatoriums to gamble as in Dostoyevsky’s The Gambler and rehabilitate as in The Magic Mountain. They built these gigantic hotels for people who might stay for months and would need everything they get at home, and more. In the age of corsets and waistcoats, mountaineering as we know it barely existed, so the hotel had to stand right next to the glacier or waterfall to be worth a visit.

Last autumn, I read First on the Rope, an old novel set in Chamonix in the early 20th century. A guide recovers from the yips, as he takes a traumatic fall while trying to rescue his father’s body. He and his comrades carry with them a profound sense of responsibility for their clients and hospitality for their guests. The French don’t have the trains or the tunnels or the cablecars like the Swiss do. The French bring guests to enjoy the mountains, but the Swiss engineer infrastructure for customers to pay for the mountains. They are not the same.

On our way up to the Matterhorn, we stopped in the hamlet of Z’mutt for lunch. Z’mutt, comprising some half dozen buildings, had but two businesses. The first, our restaurant, served us a tasty salad with sliced steak. The second was two middle aged guys in high-visibility orange uniforms who, over the course of our 90-minute lunch, moved just two pieces of roof slate into place.

Further along our hike, we passed through another hamlet, unnamed. Here, nothing was open for business, but we saw a middle-aged woman sitting on her porch with a cup of coffee, admiring her garden and her view of the most iconic mountain on earth. I narrowed in on my answer.

Switzerland has never been conquered because it’s neutral, and it's neutral because it’s never been conquered. The Basel townhomes attest to this fact, and nobody’s ever heard of the firebombing of Zurich.

As with everywhere else, some people are greedy, others are not. There’s a high school in Visp that appears to be named after Sepp Bladder, the famously corrupt FIFA head who awarded the World Cup to Qatar. This neutrality and the inaccessibility of the mountains made sure that nobody took the Swiss pots of gold. Eventually, some people turned theirs into gondolas to nowhere, which paid for themselves many times over.

Others left theirs plastered into the walls of their 700-year-old townhome. Some savvy folks buried theirs under their chalet so they could sit around all day, sip coffee, and stare up at the Matterhorn.

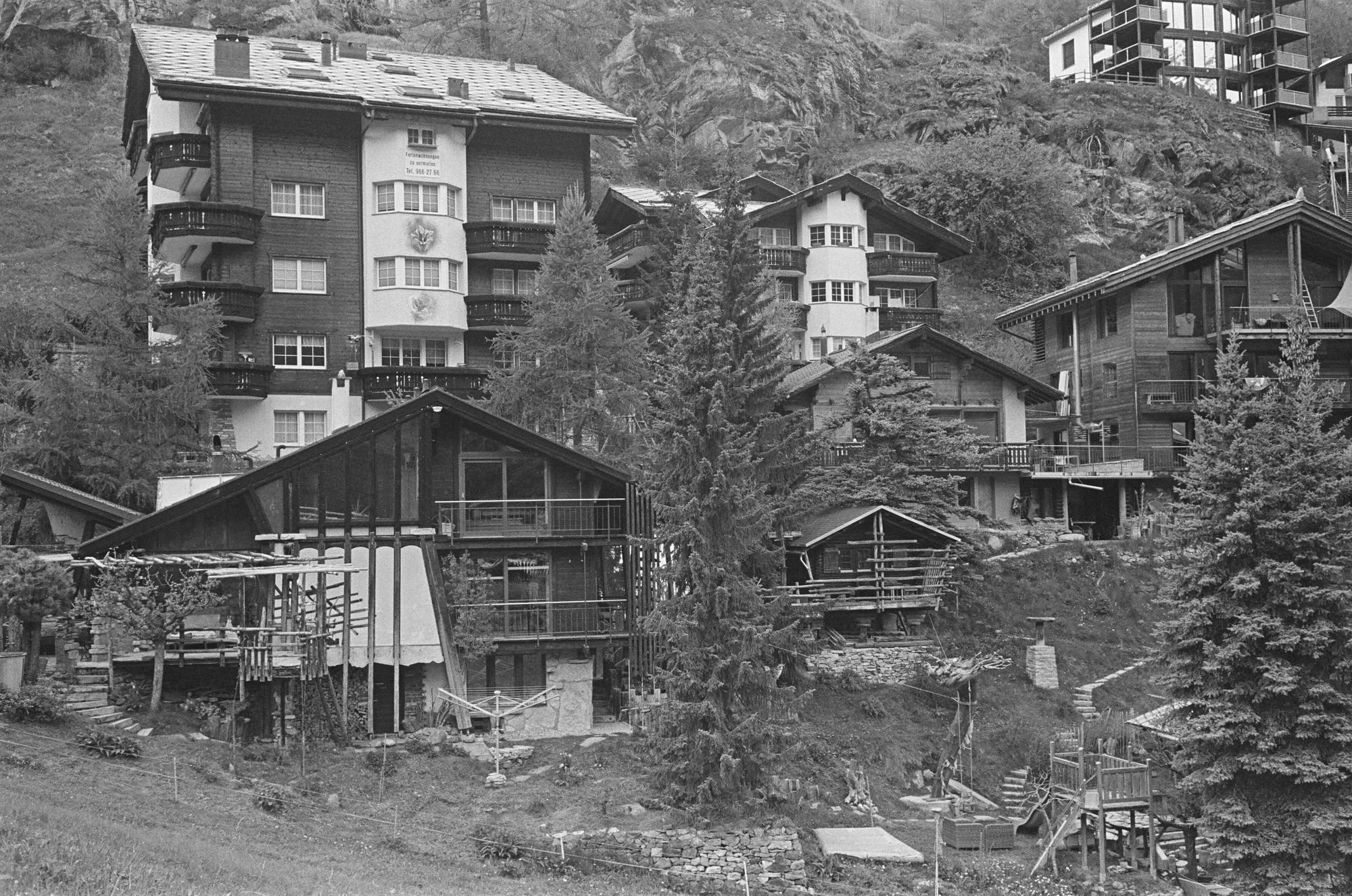

In Zermatt, the oldest houses stand on stilts to allow the snow and meltwater to run underneath. They still use slate rocks piled up for roofing. They're weatherproof, despite their age.

Here and in Grindlewald, the grazing animals get driven between the high and low meadows depending on the season. There are homes that stand at the wrong end of seven flights of hillside stairs.

Big Switzerland might be scamming unsuspecting tourists on rail tickets to places they don’t need to visit, but those two construction workers were paid by the hour with benefits to spend their 50s on long cigarette breaks, sunbathing beneath the Toblerone logo atop the roof they weren’t building. These two workers were some of the best mountaineers in the world.

The check came, and we owed some $60-worth of francs for the salad, bread, and a lemonade. The real answer. The money, all this largesse in Switzerland, it was coming from me.

Five hours later, and Emily and I were soaked through with snow, sheltering from the wind at the Schwarzsee at the top of a gondola that was supposed to be running. We knocked on the doors of the hotels, rang the bells at the restaurants, without a soul to be found. We took a rest, eating some bread to steel ourselves for the way down, debating how many hundreds of dollars we’d pay not to have to walk.